How does wong kar wai make a film?

by remi mourany

·

Wong Kar Wai, undoubtedly the foremost figure in modern Chinese cinema, is renowned for his poignant portrayal of love on screen. His films delve into tragic love stories, while also expressing an unwavering affection for his hometown, Hong Kong.

Luck plays a significant role in encountering the perfect individual, precisely when and where it's meant to happen. This sentiment, articulated by Wong Kar Wai, resonates deeply, as he arguably excels more than any other filmmaker in capturing serendipitous encounters within a cinematic landscape enriched with vibrant city life and profound love.

Undoubtedly, he stands as one of the paramount directors of the past three decades, leaving an indelible mark on the annals of cinema. Whether you're yet to acquaint yourself with his work or already an avid enthusiast of his craft, delving into his films promises a journey of rediscovery from a fresh perspective.

Today, we embark on an exploration of Wong Kar Wai's filmmaking process, delving into 10 pivotal facets: storytelling, character direction, costume design, set creation, cinematography, photography, color palette, editing techniques, sound blending, and musical composition.

PART 1 // STORYTELLING :

Wong Kar Wai's scripts always evoke love stories. It's about telling the birth of feelings, the daily life within the couple, or the heartache, the break up, that the hero must learn to overcome.

In a general way, by the way, the challenge that all these characters face is to manage to fight their sadness. Wong Kar Wai's films are therefore meetings, They stage the discovery of the other, or the reunions. They also always have several protagonists, whose paths cross but also always evolve in different directions.

These films are mostly divided into several parts, which constitute so many different plots: "Chungking Express" For example, contains two parts in which the protagonists are not the same. In "My Blueberry Nights", Elisabeth's adventures are divided into three parts, which also change the protagonists and the problems.

The rhythm of life of these characters cross, associate and oppose each other, a theme that they also develop in their films is that of living the lives of others. In 'Fallen Angels", Wong's partner, the protagonist of the first story, frequents the same bar as him and also sits in the same place. In "Chunking Express", Faye watches the apartment of the man she is in love with.

And perhaps the most obvious, in "In the Mood for Love", the two protagonists simulate the meeting between their two spouses who cheat on them. Understanding the other, by love or by grief, seems essential for the characters of these films, while we follow the evolution of their feelings. The considerations related to the couple also seem to evolve over time, in Wong Kar Wai's cinema, the passion that animates his films to "Happy Together" seems to give way to resignation from "In The Mood For Love".

But all are the common point to make us share the point of view of the victims of love, of broken hearts. If we take "My Blueberry Nights" for example, when Arnie drowns in alcohol following the separation with his wife, we follow the story on its side. But when he dies, we sympathize with the pain of his ex-wife.

As for all his films, we find in "My Blueberry Nights" the structure in several parts, in which the problems are very different, because the characters take paths that cross but do not always join. Finally, love being always ambiguous, the ends of his films are too.

PART 2 // THE CASTING

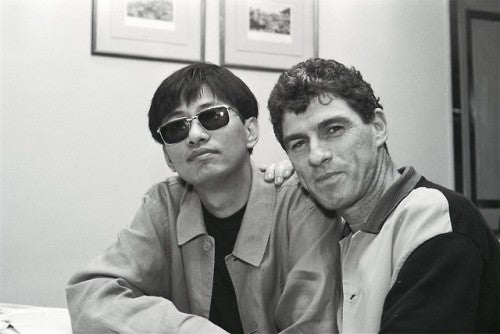

Certainly, Wong Kar Wai's meticulous direction of actors and characters is a hallmark of his filmmaking style. He often collaborates with a core group of talented actors, including Jackie Cheung, Maggie Cheung, Leslie Cheung, Carina Lau, Faye Wong, and the iconic Tony Leung, who has graced the screen in seven of his films.

In Wong's cinematic universe, the main actors typically deliver nuanced performances characterized by subtlety and restraint. Their expressions are often understated, with emotions simmering beneath the surface until they erupt in moments of heightened drama.

What sets Wong's approach apart is his keen eye for contrast and complexity within character portrayals. Tony Leung, for example, seamlessly transitions between roles, moving from the brooding protagonist in "As Tears Go By" to the enigmatic policeman in "Days of Being Wild." Similarly, his portrayal of a reserved law enforcement officer with the badge number 223 in "Chungking Express" stands in stark contrast to his portrayal of Qi Wu, a former prisoner also associated with the number 223 in "Fallen Angels";

Moreover, Wong's characters are not static; they evolve and reveal layers of depth as the story unfolds. Initially defined by their first impressions, they gradually unveil hidden complexities shaped by the whims of fate, chance encounters, and the intricacies of human connection. This thematic exploration of destiny and interconnectedness is a recurring motif that permeates Wong's storytelling from the outset, setting the stage for captivating and multi-dimensional character journeys.

PART 3 // THE COSTUMES

Wong utilizes costumes as a simple yet effective tool for character identification. Whether it's their profession or the elegance of their attire, costumes play a pivotal role in shaping the identity of each character.

Moreover, costumes often serve as symbols of character development and narrative progression. Take, for example, the apparent confidence of Bai Ling in "2046" which gradually diminishes as the story unfolds, mirrored by the decline in the elegance of her attire. Similarly, in "Chungking Express" the police officer with badge number 663 initially appears in his uniform before transitioning to a casual shirt, reflecting his evolving emotions as he falls in love with Faye.Yet, costumes also take on a central role in the plot of Wong's films. In "In The Mood For Love" it's the bag and tie of the protagonists that serve as harbingers of the deception they face. In "Days of Being Wild" it's the earrings that spark the initial encounter between Yudi and Leung, foreshadowing the trajectory of their relationship.

Furthermore, costumes serve as visual cues that reflect the inner state of characters. For instance, Yudi's attire evolves from a radiant light blue dress during the early stages of her relationship to somber black attire during moments of tension and heartbreak. Conversely, her return to colorful clothing signifies her renewed optimism after reconciling with Leung.

In essence, the costumes in Wong Kar Wai's films serve as extensions of the characters themselves, illustrating their true nature or the image they wish to project to others. Beyond mere aesthetics, they are integral elements of the narrative, enriching the storytelling experience and inviting deeper contemplation on themes of identity and self-expression.

PART 4 // HONG KONG

The primary backdrop of Wong Kar Wai's cinematic universe is the bustling city, with Hong Kong taking center stage, serving as both the director's hometown and the predominant setting for the majority of his films. It's a city of skyscrapers, but unlike conventional cinematic portrayals, Wong eschews grandiose landmarks in favor of capturing the pulse of urban life. His lens focuses on the people who inhabit these streets, capturing the essence of everyday encounters and mundane moments.

Throughout his body of work, two recurring settings stand out: the apartment and the bar or restaurant. The apartment serves as a symbolic anchor, recurring in films like "As Tears Go By" "Chungking Express" "Fallen Angels" "In The Mood For Love" and "2046" Meanwhile, the bar or restaurant becomes a hub of tension and connection, featuring prominently in pivotal scenes across various films, such as "Happy Together" "Chungking Express" and "My Blueberry Nights";

An intriguing departure from this urban focus is seen in "Happy Together," where the narrative unfolds predominantly in Argentina, particularly in Buenos Aires. Here, the characters grapple with a sense of suffocation, mirrored in the claustrophobic confines of their apartment, which serves as a poignant reflection of their individual loneliness and the emotional distance between former lovers.The passage of time, symbolized by the ticking of a digital clock against the city backdrop, underscores the characters' sense of anxiety and displacement in this unfamiliar environment. Through his films, Wong Kar Wai skillfully intertwines his characters' quest for identity with the broader canvas of the city, exploring themes of belonging, cultural duality, and the longing for emancipation in a rapidly changing world.

PART 5 // CINEMATOGRAPHY

PART 6 // PHOTOGRAPHY

PART 7 // COLOR PALETTE

Colors in his movies often convey complex and ambiguous emotions, despite their saturated and unified appearance. Wong Kar Wai masterfully uses colors to paint his scenes, typically highlighting four primary hues: blue, green, yellow, and red. While these colors do not always send specific emotions, they are notably dominant in certain films.

For example, blue is the dominant color in "Chungking Express." Everything is bathed in blue hues, from the streets of Hong Kong to the Midnight Express snack bar where the male protagonists cross paths. In "Days of Being Wild" green is the prevalent color. It saturates the jungle scenes and extends into less obvious places like the interiors of apartments and the streets navigated by Tide and Su.After the black and white opening, "Happy Together" transitions into a yellow palette, found in the protagonist's apartment, cars, streets, and sunlight. Each of these films also contains exceptional scenes that deviate from their dominant color palette. For instance, the scene with the blonde woman in "Chungking Express" the flashbacks of Yuddy in "Days of Being Wild" and Lai's distress on a boat in "Happy Together."

However, a striking example of Wong Kar Wai's use of color is found in "In The Mood For Love" which prominently features red. The color red is introduced in the opening credits and gradually becomes more pronounced throughout the film. Initially, shades of pink and purple dominate, with red appearing subtly in the apartment as orange or brown tones. As the film progresses, red becomes more prominent, seen in the female character's clothing and the male character's tie. It becomes the color of small elements like gifts and curtains before encompassing the bench where the protagonists sit and the space around them.

A pivotal shot encapsulates the film's emotional intensity, where everything in the frame is red—her lips, her dress, and the background. This shot symbolizes the passion between the characters and marks a turning point in the film. The red hues in this shot also diverge into two directions: pink or purple on the left, and orange or yellow on the right. These colors represent the different paths the characters must choose, visually separating their journeys.

In this single shot, the film's dynamics are encapsulated: the connection and eventual separation of the protagonists. For Wong Kar Wai, colors are not just aesthetic choices; they illustrate the film's narrative trends and character directions. He uses colors to develop the story, create ruptures, and imbue the film with deeper meaning and sensation.

Colors in Wong Kar Wai's films, therefore, are powerful storytelling tools. They reflect the characters' emotional states, guide the narrative direction, and enhance the visual poetry of his cinematic world.

PART 8 // EDITING TECHNIQUES

Editing is, for Wong Kar Wai, the best way to stage one of the main elements of his cinema: time. Unlike many filmmakers, Wong fully utilizes the capacities offered by cinema, especially in terms of editing.

He employs slow motion, fast motion, stop motion, jump cuts, fade-ins, and shot sequences. Editing, for the filmmaker, is a way to manipulate time, defining the rhythm of his films. Wong uses it to interweave different periods, creating a dialogue between them. For instance, at the end of "My Blueberry Nights" a man exits a café, and just as the door is about to close, it is held open by Lizzie's hand, indicating her hesitation to enter at an earlier time.

This concept is also evident in "2046" where fast-paced editing expresses the passage of time, while slower editing captures emotional depth. Similarly, in "Happy Together" the growing impassivity of a character is emphasized by the length of the take.

Wong’s use of slow motion is notable, as seen in "Ashes of Time" with the arrival of horsemen. However, the most remarkable example is in "Chungking Express" where Wong employs a technique called step printing. This involves the repetition of an image over several frames per second, giving the film a unique rhythm—making a slowed-down image appear accelerated or vice versa.

This technique is used at the beginning of the film to highlight the encounter between the protagonist and the woman with the blonde wig, which neither of them notices in real time. Cinema allows the viewer to perceive this encounter, making it significant. Wong Kar Wai uses editing as a tool to engage the viewer, creating an awareness of its artificiality while making it essential for understanding the film. For Wong, editing is a way to communicate directly with the viewer, not through words, but through the language of cinema.

PART 9 // SOUND BLENDING

As the city is a character in all his movies, the sound transmits the spirit of urban movement: the cars, the horns, and the voices of its inhabitants. Background noise is always present to mark the city's activity. This noise continues inside, where the sounds of the city persist.

Whether it's the activity of cars, the presence of a television, or music accompanying the characters, the urban soundscape is ever-present. One distinctive choice in his cinema is the use of voiceovers to narrate the story from the heroes' perspectives. These narrations, always in the first person, invite us to listen to the protagonists' stories.

Sometimes multiple voice actors dialogue, as seen in "Chungking Express" representing the crossing of characters' paths. However, the use of sound we will focus on is in fight scenes, where Wong Kar Wai often employs a technique called step printing. Here, the fights are accompanied by sounds that represent the scene we are witnessing, yet these sounds are not synchronized with the images on screen.

While the image is cinematic, the sound mixing closely transcribes reality—or at least what our imagination perceives as reality. This mixing often contrasts with the editing, as in a striking scene where vivid editing is juxtaposed with an overlay of sound.

Voices, creaking floors, birds, violin strings, and screams—all out of sync with the images—create a unique audio-visual experience. Wong Kar Wai uses sound mixing to oppose the editing. In his cinema, it is the sound that most faithfully reconstitutes the reality of events, while the editing offers a more poetic or romantic vision.

PART 10 // MUSICAL COMPOSITION